Software, code, and repositories

Published:

A short thread on software, code, versioning, citation, and repositories. Only very few AEA articles reference Github/Gitlab/Bitbucket repositories. More should do so. A few notes.

Replication packages and version control

Fact: all replication packages contain code.

Note: sometimes, that’s an Excel file, but that’s still code.

But few seem to stem from version control repositories. The most common version control software these days is git, though I’ve seen a few uses of svn. Both are popular because they usually come accompanied by online web services that allow authors to showcase their code, as well as conduct a few other key functions that I will get to.

By far the most popular as of 2021 is Github - in fact, this blog post and website are hosted on Github-provided resources. Others include Gitlab, Bitbucket, and for svn, SourceForge.

Version control allows for, well, version control. This is particularly relevant for replication packages, since code probably is evolving. Which version was used to generate the tables and figures in the paper is very important information.

While authors are able to “lock in” a version that was used when they submit to the AEA Data Editor (via AEA Data and Code Repository), ideally, that version is locked in prior to submitting.

Locking in versions

If using version control, creating a “locked in” version that corresponds to a particular version of the paper is easy. It may be called different things (“releases” on Github and in svn, “tags” in native git), but it achieves the same function: It marks a particularly version of code.

That tag can contain additional “metadata” - an “annotated tag” or a “Github release” can be quite verbose. But in all cases, the key is to uniquely identify the version of the code that was used to do something, or that corresponds to something.

NOTE: strictly speaking, those tags are not necessary. Authors could simply point to a particular “commit hash”, e.g. “https://github.com/<user>/<project>/tree/<hash>” to uniquely point to a particular version as well (similarly on svn, pointing to revision numbers). But tags are a tad more human readable than https://github.com/AEADataEditor/replication-template-development/tree/7634e14ee9a0a433db1ab6f25609dfb4c6876483.

Archiving Versions

Once authors have identified a particular version of the code, there remains of course the issue that Github & Co. are not “trusted repositories”. So authors will still need to somehow archive that particular version.

One convenience of using features like “Github releases” or even tags on Github is that the interface provides a convenient link to download a ZIP or TAR file without all the extra git information.

Once you have the ZIP or TAR, you can manually send this off to a trusted repository. That’s what most authors are or should be doing when submitting to the AEA Data and Code Repository, or for that matter for any journal’s supplementary materials archive.

However, that is tedious, and at least for Github, there is a different (automated) option: linking it to Zenodo. Authors should consult the (very easy) details in the link, but in a nutshell, this is what happens:

- you set up the link. Takes a bit of work the first time, but then it’s done, forever.

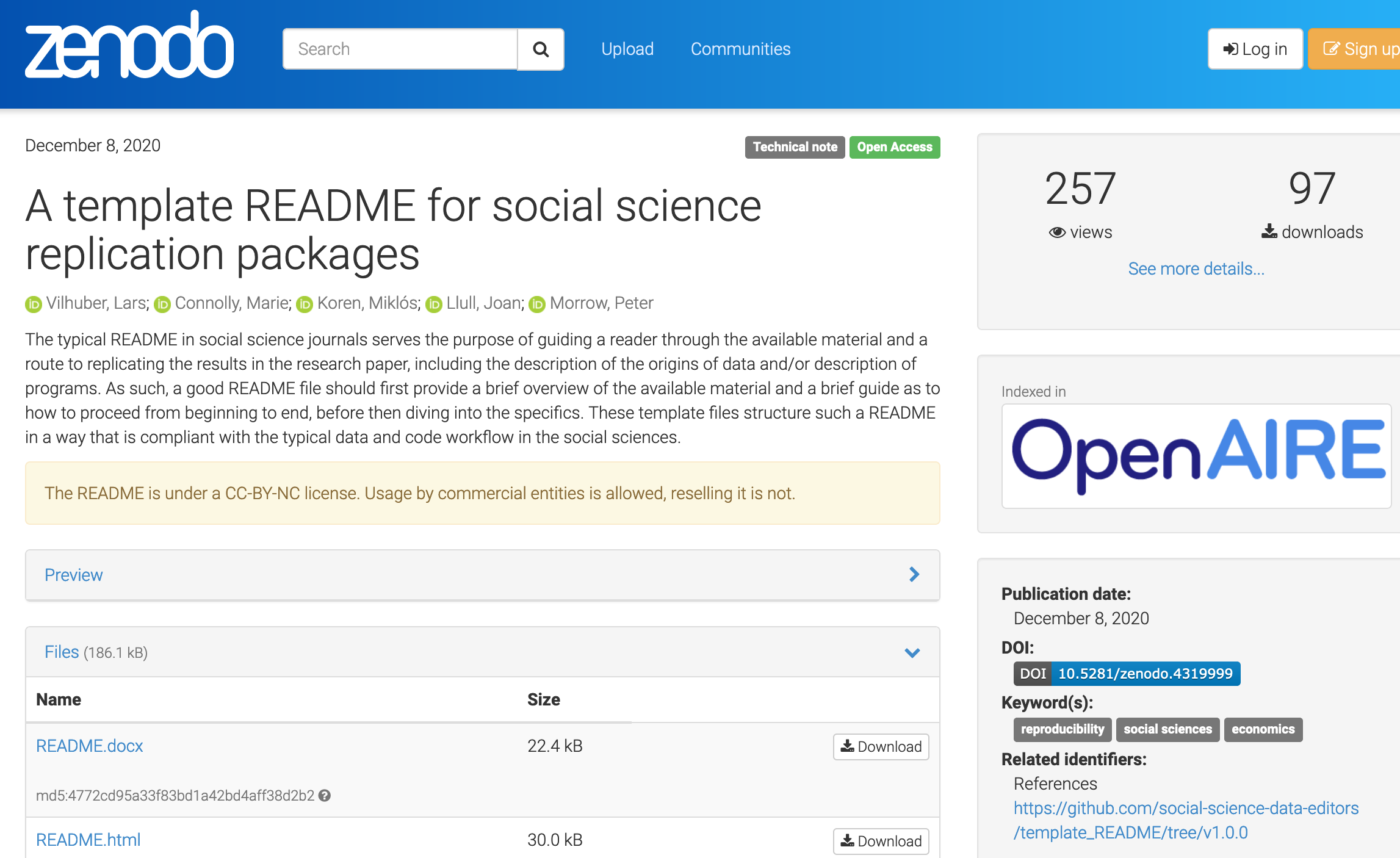

- every time a release is made, the ZIP file is sent automatically to Zenodo, and creates an archive, with a DOI and a preservation guarantee.

- The Zenodo deposit links back to the particular release/tag on Github

- some cosmetic editing (to Zenodo metadata, to eye candy such as a DOI badge) can make it pretty, but are not needed.

Example

For an example see

- the source code for template README on Github, including any releases

- the page generated from the source code on Github.io

- the “badge”:

- the archived version on Zenodo

The version - in fact, any future version - is now properly archived at a trusted repository.

Citing Software Versions

Last but not least, but in particular when the code authors generated is of more general utility (a Stata or R package for a new econometric technique), citing the software is a must (see FORCE11 Software Citation Principles,1)

By creating archived versions, Zenodo, or any other trusted repository, provides a DOI that can then be cited:

Smith, A. and J. Wesson. 2021. “15-fold quantum fixed effects, R package.” v0.2-alpha. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zen0do.12345

Naturally, authors could also cite the Github-hosted version, but only with the authority of a (transient, ephemerous) website:

Smith, A. and J. Wesson. 2021. “15-fold quantum fixed effects, R package.” v0.2-alpha. Github. Last accessed at https://github.com/smith-wesson/cdqfe/releases/tag/v0.2-alpha on June 17, 2025.

-

Smith AM, Katz DS, Niemeyer KE, FORCE11 Software Citation Working Group. 2016. Software Citation Principles. PeerJ Computer Science 2:e86. DOI: 10.7717/peerj-cs.86 ↩