Some remarks on challenges and solutions when conducting reproducibility checking for two recent AEJ:Applied articles

Published:

I wanted to briefly discuss the challenges when conducting data provenance and reproducibility checks, for complex and highly interesting articles, with the example of two articles in the most recent (April 2023) issue of the American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. The solutions involved online compute capsules and alternative repositories.

The two articles are

-

Infrastructure Costs (Leah Brooks and Zachary Liscow)

-

DETER-ing Deforestation in the Amazon: Environmental Monitoring and Law Enforcement (Juliano Assunção, Clarissa Gandour and Romero Rocha)

Each of these articles posed a different challenge to my team. In all cases, they are highly complex analyses with large, sometimes very large, data sources.

Using Zenodo to augment primary replication packages

First, let me consider the impressive work by Leah Brooks and Zachary Liscow, “Infrastructure Costs”.

The paper conducts an investigation of the cost of building the US Interstate Highway System, from the 60s to the 80s. There are a lot of miles in the Highway system (about 49,000 miles or 79,000 kilometers), and their data covers a long time period in which much data was not necessarily easily available as digital records. As they so blithely say, “we digitize annual state-level spending data from 1956 to the present… first to use more than a few years of these data…”. While that’s already a lot, they also use the “USGS National Map 3DEP 1-Arc-second Digital Elevation Models” and “National Wetlands Inventory of the United States - State and Substate Shapefiles” (among others) in the analysis. Each of these sources have several hundred files and several dozen gigabytes of data:

| Component | Size (GB) | Count (files) |

|---|---|---|

| USGS National Map 3DEP 1-Arc-second Digital Elevation Models | 83.8 | 3449 |

| National Wetlands Inventory of the United States - State and Substate Shapefiles | 49.3 | 150 |

| Remainder of the replication package | 18.53 | 940 |

While both of these sources are in the public domain, they are large, and were, in fact, augmented by the authors.

Two problems arose for us: how do we make these data available to others, and how do we highlight the value-added that the authors have contributed?

The first problem arises because openICPSR, the repository used as the primary deposit for AEA replication packages, does not handle deposits of more than 20GB gracefully. As of 2023, it is slow to create such deposits, and very slow for others to re-use these packages. There also appear to be hard limits around 30GB and 1,000 files.

The second problem is a more philosophical one. While anybody can go back to USGS or the US. Fish and Wildlife Service to obtain these data, most US government agencies do not properly curate or preserve their data. These data may not be there, or they may no longer be there in this format. In fact, for the USGS data, the authors used DVDs that were originally purchased from the US government, augmented by targeted downloads from an interactive, non-scriptable downloader, to fill in missing rasters.

We addressed both of these problems by creating two auxiliary deposits on Zenodo, and removing the data from the primary replication package on openICPSR. The resulting two Zenodo archives are part of the (growing) American Economic Association community on Zenodo:

- U.S. Geological Survey, & Brooks, Leah. (2022). “USGS National Map 3DEP 1 Arc-second Digital Elevation Models (DEMs): Full Coverage for U.S. Interstate Highway System [Data set].” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5830968

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. (2022). “National Wetlands Inventory of the United States - State and Substate Shapefiles (Version v2018) [Data set].” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5823387

While downloading nearly 130GB of data from any repository can still be challenging in time and robustness, these data resources are now available.

Tools that we used

- Zenodo uploader via API, originally written by a former RA, to upload all files.

zenodo_getto re-download thousands of files.

Oh, and because it still takes over 250GB of local disk space and substantial processing time to reproduce the replication package, this is one of the replication packages that we inspected (deeply), but which we did NOT actually run. However, we are confident that a replicator with sufficient resources (including time) can do so. Nevertheless, should a replicator encounter issues, please do contact us, and we will, in turn, contact the authors, if appropriate, to update their replication package as per our revision policy.

Using compute capsules for easy reproduction

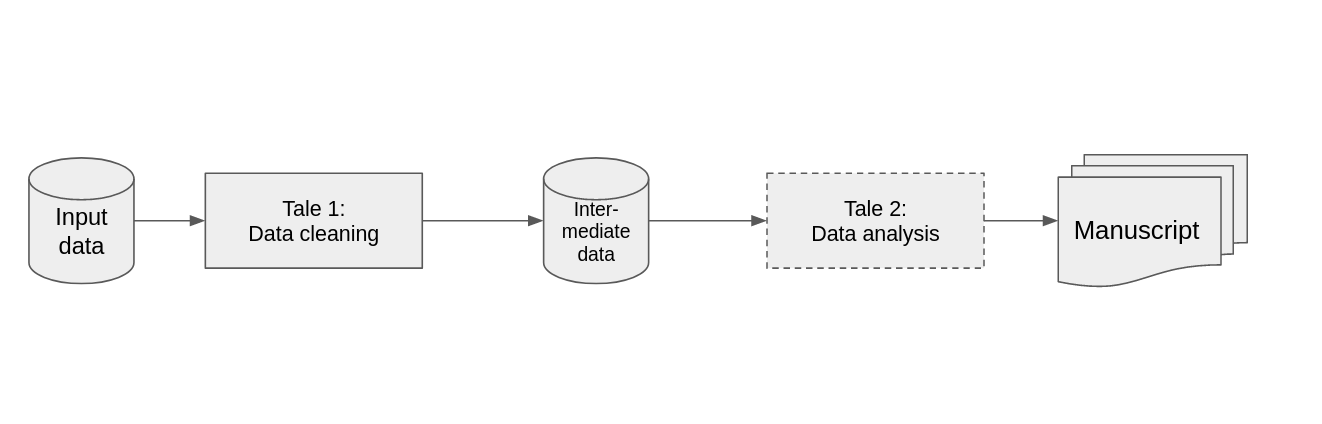

I have previously discussed the use of Docker in economics. In “DETER-ing Deforestation in the Amazon: Environmental Monitoring and Law Enforcement”, Juliano Assunção, Clarissa Gandour and Romero Rocha collect a whole lot of publicly available Brazilian data, clean it all, and for this article, analyze a particular aspect of it (cloud cover preventing the DETER system from working in a particular area). Because this is a part of what their home institution (the Climate Policy Initiative) does regularly, the data cleaning is part of a data processing pipeline, and run in R. The analysis, as with so many analyses created by economists, runs in Stata.

While it is possible to create a pipeline using both R and Stata, either by combining multiple containers in sequence, or by combining Stata and R in the same container, this is typically not possible (or very hard) in the easy-to-use online interfaces to Docker such as CodeOcean and Wholetale. However, in this case, we wanted to make the analysis easily accessible to others. That also argued against combining the two parts into a single compute capsule: the data processing takes about three weeks, while the core analysis only takes a few minutes.

So in coordination with me, the authors (corresponding author Clarissa Gandour) split the analysis out in a self-standing “capsule” (https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.5098352.v1), while the whole processing pipeline is made available in the main replication package on openICPSR (https://doi.org/10.3886/E132281V1). Interested replicators can go through the whole data cleaning process (as required by our policy), but if instead they want to focus on the analysis, they can do so with a couple of clicks in CodeOcean.

They can, of course, also run the analysis on their own computer, either following the instructions in the README while running with their own copy of Stata, or running it on their own computer through Docker, using the CodeOcean-provided container combined with their own license.

In this case, we did not run the final version of the data cleaning pipeline, because we inspected the code, ran parts of it, and assessed that it was reproducible (we had run the first draft of the data cleaning pipeline, and sent the authors our feedback). We also did not run the analysis part - not because it’s not feasible, but because the authors ran the analysis on CodeOcean to produce the output in the manuscript. It is that output - together with a screen capture of Stata as it is chugging along - which is visible in the CodeOcean interface:

We thus did not need to run it, because the authors had run it in an environment which we know is fundamentally reproducible.

Tools that we used

- CodeOcean - academic users have 10 free hours per month

- Docker on local machines, to test the independent reproducibility of the package

- including the Docker Stata image that I prepare

What are still unsolved issues in these scenarios

The two articles illustrate a few key points when it comes to larger-than-usual analyses. First, despite the size of the data, it is feasible to archive and preserve the data in ways that makes it usable for others. However, neither article is fully integrated, when theoretically that is possible. In the Brooks and Liscow article, the current version of the code does not dynamically download the Zenodo-hosted data - that is a manual process. In the Assunção, Gandour, and Rocha article, the data cleaning pipeline is not in CodeOcean, because in the end, the authors would still have needed to copy the output from their data cleaning into the analysis capsule.

Would it be possible to chain two CodeOcean capsules - one running the “DETER” three-week data cleaning pipeline, the other the 5 minute data analysis code?

As of 2023, it is not, at least not in the public product (it is a feature of CodeOcean’s on-premise solutions, however). Could the Brooks and Liscow article have integrated data storage on Zenodo from the start? Solutions that do so exist (see Snakemake and one of its front-ends show your work!), but are rarely seen in economics (and come with their own reproducibility demons).

The Assunção, Gandour, and Rocha capsule is, however, an example of how porting the analysis code for the article, and then using it as the primary interface for the final versions is feasible.

While time-consuming, the upload of some of the key value-added files from the Brooks and Liscow article have already proven useful to others - while the original replication package has had 34 unique visitors, the Zenodo-hosted data have had 173 and 103 unique visitors as of this writing! Whether this ultimately leads to more citations (another metric that apparently some folks care about) remains to be seen in the future.

Disclosures

As noted, CodeOcean currently offers academics 10 hours of compute time per month for free. They have also supported the Data Editor’s work with a generous compute quota (which allows us to run weeks-long analyses). I am neither paid, nor do I detain any shares in CodeOcean, nor do I receive a commission for any new customers signing up for a CodeOcean account (which in fact is free). Docker is a commercial company, and I am a paying individual subscriber in order to host container images that the AEA uses. Running containers on personal computers remains free, and running containers on most Linux servers is also free (there are many ways to run containers, not just using Docker’s runtime). Wholetale is an academic infrastructure funded by the National Science Foundation. I have been part of such funding in the past through a subaward, and am currently collaborating with the maintainers of Wholetale on a project that, if successful, would be beneficial to Wholetale. And CodeOcean. And a bunch of other computing infrastructures around the world. Wholetale is free to use, without limitations.

References

- Assunção, Juliano, Clarissa Gandour, and Romero Rocha. 2021. “Replication Capsule for: DETERring Deforestation in the Amazon: Environmental Monitoring and Law Enforcement.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.5098352.v1.

- ———. 2023. “DETER-Ing Deforestation in the Amazon: Environmental Monitoring and Law Enforcement.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 15 (2): 125–56. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20200196.

- Brooks, Leah, and Zachary Liscow. 2023. “Data and Code for: Infrastructure Costs.” [Replication package]. American Economic Association [publisher], 2023. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]. https://doi.org/10.3886/E144281V1.

- ———. 2023. “Infrastructure Costs.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 15 (2): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20200398.

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. 2022. “National Wetlands Inventory of the United States - State and Substate Shapefiles.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5823387.

- U.S. Geological Survey, and Leah Brooks. 2022. “USGS National Map 3DEP 1 Arc-Second Digital Elevation Models (DEMs): Full Coverage for U.S. Interstate Highway System.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5830968.

.